Book Appoinment

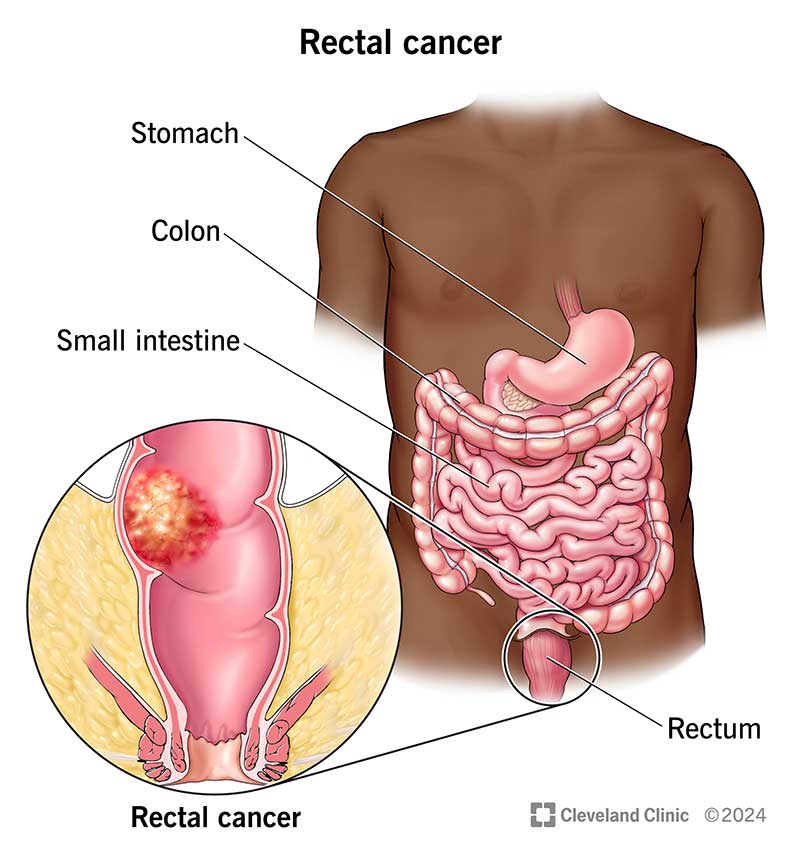

Rectal Cancer

Rectal cancer happens when cancerous cells develop in your rectum. Symptoms include rectal bleeding or changes in how and when you poop. Having a biological family history of rectal cancer or certain inherited disorders increases your rectal cancer risk. Treatments include surgery to remove cancerous tumors, chemotherapy, radiation therapy and targeted therapy.

Overview

What is rectal cancer?

Rectal cancer typically is a slow-growing cancer that forms on the inner lining of your rectum. Your rectum is the last several inches of your large intestine. Most rectal cancers start as clumps of abnormal cells (polyps) known as adenomas. It can take 10 to 15 years for a polyp to turn into a cancerous tumor on your rectum.

Cancer screening like colonoscopies often detect polyps that can become cancer. Regular screenings to detect and remove polyps reduce your risk of developing rectal cancer. If you have rectal cancer, surgery to remove small cancerous tumors may cure the condition.

Rectal cancer, also known as colorectal cancer when it affects the rectum or colon, can present with a variety of symptoms. Early detection is crucial for effective treatment, so recognizing these symptoms can be vital. Here are common signs and symptoms to be aware of:

Rectal cancer is the third most common cancer in your digestive system, behind colon cancer and pancreatic cancer. Experts estimate 46,200 people will receive a rectal cancer diagnosis in 2024.

Symptoms and Causes

What are rectal cancer symptoms?

You can have rectal cancer for years without noticing changes in your body. In many cases, rectal cancers don’t cause symptoms at all. However, some people may notice certain warning signs. Rectal cancer symptoms may include:

- Rectal bleeding.

- Diarrhea.

- Constipation.

- A sudden change in how and when you poop.

- Poop that looks stringy or as thin as a pencil.

- Tiredness.

- Weakness.

- Abdominal pain.

- Unexplained weight loss.

What causes rectal cancer?

The exact cause of rectal cancer is unknown. But there are certain risk factors that increase your chance of developing the disease, including:

- Age: Like most cancers, the risk of rectal cancer increases with age. The average age of diagnosis is 63.

- Certain diseases and conditions: Several health conditions can increase your risk for rectal cancer, including inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

- Eating processed meat: People who eat a lot of red meat and processed meat have a higher risk of developing rectal cancer.

- Family history: If you have a biological family member who’s been diagnosed with rectal cancer, your chance of developing it is almost double.

- Gender: Men and people assigned male at birth are slightly more likely to develop rectal cancer than women and people assigned female at birth.

- Inherited colorectal cancer syndromes: Inherited conditions that increase rectal cancer risk include Lynch syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), MUTYH‐associated polyposis (MAP), juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome.

- Obesity: People who have obesity are more likely to have rectal cancer compared to people who don’t have obesity.

- Race: Statistically, people who are Black are more likely to develop rectal cancer. The reasons for this aren’t fully understood yet.

- Smoking: Recent research suggests that people who smoke tobacco are more likely to die from rectal cancer than people who don’t.

Diagnosis and Tests

How is rectal cancer diagnosed?

Diagnosis begins with routine screening tests, including digital rectal examination (DRE) and colonoscopy. Your provider may do a biopsy during your colonoscopy to obtain tissue samples for examination by a pathologist.

If lab tests detect cancer, your provider may refer you to an oncologist for additional tests. Those tests may include blood tests, imaging tests, procedures to confirm diagnosis, and lab tests for closer examination of cancerous cells in tissue samples.

Blood tests

Your oncologist may order the following blood tests to look for signs of rectal cancer:

- Complete blood count (CBC): A medical pathologist may check your red blood cell levels for signs of anemia.

- Comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP): This test measures many substances in your blood, including ones that show how well your kidneys and liver are functioning.

- Liver enzyme test: This test checks for signs that rectal cancer is in your liver.

- Tumor marker tests: A tumor marker is a substance that cancerous cells may release in your blood. In rectal cancer, a medical pathologist will look for signs of carcinoembryonic antigens (CEA).

Diagnostic procedures

Tests may include a diagnostic colonoscopy, which follows up on the test that detected abnormalities in your rectum. They may order a proctoscopy to look inside your rectum.

Imaging tests

Your oncologist may order the following imaging tests to determine if cancer is spreading (metastasizing) from your rectum to other areas of your body:

- Computed tomography (CT) scan.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) tests.

- Pelvic ultrasound.

Your oncologist will use test results to establish the cancer stage. Rectal cancer is categorized into five different stages:

- Stage 0: Screening tests detect cancerous cells on the surface of tissue lining your rectum.

- Stage 1: The tumor grows below the lining and possibly into your rectal wall.

- Stage 2: The tumor grows into your rectal wall and might extend into tissues around your rectum.

- Stage 3: The tumor invades your lymph nodes next to your rectum and some tissues outside of your rectal wall.

- Stage 4: The tumor spreads to distant lymph nodes or organs.

Management and Treatment

What are treatments for rectal cancer?

Depending on your situation, your provider may do active surveillance. In active surveillance, sometimes known as watchful waiting, your provider carefully monitors your overall health and symptoms.

They may also do other treatments, including surgery. Surgery to remove cancerous tumors is one of the most common rectal cancer treatments. Your colorectal surgeon may consider several options, including:

- Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEMS): During this procedure, your surgeon removes small cancers from your rectum using a special scope inserted through your anus. They may recommend this treatment if the tumor in your rectum is small and not likely to spread.

- Low anterior resection (LAR): If the tumor in your rectum is large, your colorectal surgeon may do LAR, removing all or part of your rectum.

- Abdominoperineal resection (APR): Your colorectal surgeon may do this surgery if there’s a tumor near your anus they can’t remove without damaging the muscles that control your bowel movements. In APR, your surgeon may remove your anus, rectum, and part of your colon. They’ll also do a colostomy so waste can leave your body.

Treatments other than surgery may include:

- Chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy.

- Immunotherapy.

- Targeted therapy.

Surgery and other cancer treatments may cause several side effects. If you’re receiving rectal cancer treatment, you may want to consider palliative care. Palliative care is specialized care that can help you manage cancer symptoms, treatment side effects and other aspects of having a serious illness.

Clinical trials for rectal cancer

Clinical trials help healthcare providers and scientists find more effective treatments for different diseases. In a clinical trial, researchers intensively study treatment options for more effective ways to treat cancer. Ask your provider if a clinical trial is right for you.

Prevention

Can rectal cancer be prevented?

While you can’t prevent rectal cancer altogether, there are steps you can take to reduce your risk. For example:

- Maintain a weight that’s healthy for you. If you’re not sure what that means, ask a healthcare provider for guidance.

- Exercise regularly.

- Avoid processed meat, while eating a well-balanced diet of lean protein, whole grains and lots of leafy green vegetables.

- Avoid drinking beverages containing alcohol.

- Don’t smoke tobacco

Regular cancer screening may reduce the chance that you’ll develop rectal cancer because screenings may detect precancerous polyps. And if you have rectal cancer, screenings may detect it while cancerous tumors are small and easier to treat. Colonoscopy is the most common screening test, but there are also other options:

- Fecal occult blood test (FOBT): This test detects hidden blood in your poop. Medical pathologists test samples of your poop for blood that you may not see just by looking.

- Guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT): Like the FOBT, this test looks for blood in poop that may not be visible.

- Fecal DNA test: This test looks for signs of genetic mutations and blood products in your poop.

- Sigmoidoscopy: This test lets healthcare providers examine the inside of your lower colon (sigmoid) and colon.

- Virtual colonoscopy: This test is a computed tomography (CT) scan that looks for polyps in your colon and rectum.

In general, people age 45 and older should have regular colorectal cancer screening tests. Ask a healthcare provider or your primary care provider to recommend when you should have screening tests. A primary care provider knows you, your family medical history and your medical history and is your best source of information.

Outlook / Prognosis

What can I expect if I have rectal cancer?

Your prognosis, or what you can expect after treatment, depends on your situation. For example, if you had APR surgery, you may need to rely on a colostomy, which changes the way that you poop.

What are the survival rates for rectal cancer?

Overall, data from the National Cancer Institute (U.S.) (NCI) shows 68% of people with rectal cancer were alive five years after their diagnosis. The NCI groups cancer survival rates from tumor location instead of cancer stage. The five-year survival rates by tumor location are:

Living With

How do I take care of myself?

Your rectal cancer journey doesn’t end with treatment: Your oncology team may want to monitor your health for several years after you finish treatment. Living from test to test can be emotionally exhausting. If that’s your situation, consider participating in cancer survivorship programs.

What are follow-up tests and test timelines for rectal cancer?

Your follow-up appointments will vary depending on your situation, and may include the following timeline and tests:

- Colonoscopy: You’ll have a colonoscopy a year after your treatment. If tests don’t find signs of cancer, you’ll have another examination in three years. If those tests don’t find rectal cancer, you’ll have a colonoscopy every five years.

- Proctoscopy: If you had TEMS to remove a tumor from your rectum, you may have a proctoscopy every three to six months for the first two to three years after your surgery. If that test reveals any abnormalities, your provider may schedule additional follow-up tests every six months for the next three years.

- Imaging tests: If your provider believes rectal cancer may come back (recur), they may recommend additional CT scans every six months to a year.

- CEA tests: You may have CEA blood tests every three to six months for the first two years after treatment and then, every six months for the next three to five years.

When should I go to the emergency room?

If you’re undergoing rectal cancer treatment, call your healthcare provider right away if you develop:

What questions should I ask my doctor?

If you’ve been diagnosed with rectal cancer, you’ll want to gather as much information as you can. Here are some questions to ask your healthcare provider:

- What stage of rectal cancer do I have?

- How far has the cancer spread?

- What are my treatment options?

- If I have surgery, will I need to have a colostomy?